The Force.

The Force doth give a Jedi all his pow’r,

And ‘tis a field of energy that doth

Surround and bind all things

Together, here within our galaxy. – Obi-Wan Kenobi, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars, Verily A New Hope, Act II, Scene 2

On July 2, 2013, Philadelphia-based Quirk Books published Ian Doescher’s William Shakespeare’s Star Wars, Verily A New Hope, the first volume in a nine-book series that reimagines the Skywalker Saga created by George Lucas as Elizabethan era stage productions written by William Shakespeare. In this non-canonical but well-crafted and witty satire, Doescher takes the 1970s-era Star Wars Episode IV: A New Hope’s familiar characters and situations from the movie screen and plunks them down on the stages of London’s Globe Theater or similar venues, using late 16th Century dramatic devices, such as a five-act structure, the use of a chorus to set the scene or comment on the action, and, of course, writing the dialogue and soliloquies in iambic pentameter.

To many readers, the notion of mashing up a space fantasy film set “a long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” made with dazzling special effects and written in late 20th Century idioms with the works of the Bard of Stratford-on-Avon boggles the mind. Many Star Wars fans might ask questions such as, “How does one depict space battles and exotic locales such as Tatooine or the fourth moon of Yavin on a stage?” and “What is the connection between Shakespeare and Lucas?” And some Shakespeare purists might have issues with blending the works of perhaps the greatest poet and dramatist in the English canon with those of a pop culture mythmaker from Modesto, California.

As Doescher, who was born a few weeks after the original film – then known simply as Star Wars – premiered in 1977 and became a fan of the franchise at age six when he saw Return of the Jedi in 1983, explains in his afterword:

William Shakespeare’s Star Wars.

At first glance, the title seems absurd.

But there’s a surprising and very real connection between George Lucas’s cinematic masterpiece and the thirty-seven (give or take) plays of William Shakespeare. That connection is a man named Joseph Campbell, author of the landmark book The Hero of a Thousand Faces.

Campbell was famous for his pioneering work as a mythologist. He studied legends and myths throughout world history to identify the recurring elements – or archetypes – that power all great storytelling. Through his research, Campbell discovered that certain archetypes appeared again and again in narratives separated by hundreds of years, from ancient Greek mythologies to classic Hollywood westerns. Naturally, the plays of William Shakespeare were an important source for Campbell’s scholarship, with brooding Prince Hamlet among his cadre of archetypal heroes.

George Lucas was among the first filmmakers to consciously apply Campbell’s scholarship to motion pictures. “In reading The Hero of a Thousand Faces,” he told Campbell’s biographers, “I began to realize that my first draft of Star Wars was following classic motifs. . .so I modified my next draft according to what I’d been learning about classical motifs and made it a little bit more consistent.”

To put it more simply, Campbell studied Shakespeare to produce The Hero of a Thousand Faces, and Lucas studied Campbell to produce Star Wars. So it’s not at all surprising that the Star Wars saga features archetypal characters and relationships similar to those foun0d in Shakespearean drama. The complicated parent/child relationship of Darth Vader/Luke Skywalker (and the mentor/student relationship of Obi-Wan Kenobi/Luke Skywalker) recalls plays like Henry IV Parts 1 and 2, The Tempest, and Hamlet. Like Sith Lords, many of Shakespeare’s villains are easily identifiable and almost entirely evil, with notable baddies including Iago (Othello), Edmund (King Lear), and Don John (Much Ado About Nothing). Still others, like Darth Vader, are more conflicted and complex in their malevolence: Hamlet’s Claudius and the band of conspirators in Julius Caesar. Destiny and fate are key themes of Star Wars, as they are in Romeo and Juliet, A Midsummer’s Night Dream, and Macbeth.

Illustration by Nicolas Delort. (C) 2013 Quirk Books and Lucasfilm Ltd. (LFL)

Between the Covers

Vader: I find thy lack of faith disturbing. – Act II, Scene 2, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars

The Shakespeare version of Star Wars retells the events of the film – from the Imperials’ capture of Princess Leia’s Rebel Blockade Runner (aka the Tantive IV) above the desert planet of Tatooine to the climactic Battle of Yavin. Like Lucas’s movie, it is the coming of age story of a young Tatooine moisture farmer, Luke Skywalker, who is torn between staying home to help his foster parents, Uncle Owen and Aunt Beru Lars, on the farm and heeding the call of adventure as the galaxy is riven in two in a civil war between the evil Galactic Empire and a band of freedom fighters known as the Rebel Alliance.

The play, which we are supposed to interpret as a play written in Shakespeare’s time, is crafted as a work for a theater with a wooden stage and the costumes, props, and dramatic styles of late 16th Century England.

Thus, in lieu of the 20th Century Fox Fanfare, the “A long time ago in a galaxy far, far away” card, and the title crawl underscored by John Williams’ Main Title from Star Wars, a chorus recites a prologue in the vein of Henry V:

It is a period of civil war.

The spaceships of the rebels striking swift

From base unseen have gained a victory o’er

The cruel Galactic Empire now adrift.

Amidst the battle, rebel spies prevailed

And stole the plans to a space station vast

Whose powerful beams will later be unveiled

And crush a planet, ‘tis the Death Star blast.

Pursued by agents sinister and cold,

Now princess Leia to her home doth flee,

Delivering plans and a new hope they hold:

Of bringing freedom to the galaxy.

In times so long ago, begins our play,

In star-crossed galaxy far, far away.

Just as Shakespeare focused on telling stories through his characters’ dialogues and soliloquies – which often “break the fourth wall” in asides that are aimed to the audience but not heard by the other characters in the play – rather than with detailed action, Doescher doesn’t write long scene descriptions with “action” elements. Instead, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars, Verily A New Hope depicts visual scenes from the source movie like so:

SCENE I

Aboard the rebel ship.

Enter C-3PO and R2-D2.

C-3PO: Now is the summer of our happiness

Made winter by this sudden, fierce attack!

Our ship is under siege, I know not how.

O hast thou heard? The main reactor fails!

We shall most surely be destroy’d by this.

I’ll warrant madness lies herein!

R2-D2: – Beep beep,

Beep, beep, meep, squeak, beep, beep, beep, whee!

C-3PO: – We’re doomed.

The princess shall have no escape this time!

I fear this battle doth portend the end

Of the Rebellion. O! What misery!

(Exeunt C-3PO and R2-D2.]

Chorus: Now watch, amaz’d, as swiftly through the door

The army of the Empire flyeth in.

And as the troopers through the passage pour,

They murder sev’ral dozen rebel men.

Doescher utilizes the Chorus to verbally describe to his “Shakespearean era” audience the various locales – including the desert wastes of Tatooine, Mos Eisley spaceport, the infamous cantina where Luke and Obi-Wan meet Han Solo and Chewbacca, the Death Star, and the Rebel base on Yavin 4 – and iconic scenes such as the Millennium Falcon’s breaking of the blockade over Tatooine and Princess Leia’s rescue from Cell 2187 by describing them briefly in narration. (In later books, the author leans less on the Chorus, after getting feedback that told him he was overusing the device a bit much.)

May the verse be with you! Inspired by one of the greatest creative minds in the English language—and William Shakespeare—here is an officially licensed retelling of George Lucas’s epic Star Wars in the style of the immortal Bard of Avon. The saga of a wise (Jedi) knight and an evil (Sith) lord, of a beautiful princess held captive and a young hero coming of age, Star Wars abounds with all the valor and villainy of Shakespeare’s greatest plays. Reimagined in glorious iambic pentameter, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars will astound and edify learners and masters alike. Zounds! This is the book you’re looking for. – Publisher’s dust jacket blurb, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope

Like Quirk Books’ best-selling Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice and Zombies, this is satire at its best. Doescher, who fell in love with the works of the real Shakespeare in middle school, uses his knowledge of Elizabethan dramatics and his affinity for the Star Wars films (he is on record as saying that Return of the Jedi is his favorite because it’s the first installment of the Skywalker Saga he saw, at age six, in its original theatrical run) to good use. Because he knows the works of Shakespeare and Lucas so well, he is able to give readers a new, non-canonical interpretation of Star Wars that’s full of puns, asides (R2-D2, for instance, sometimes will break the fourth wall and address the audience in English, mainly to comment on another character’s – usually C-3PO or Luke’s – predicaments), inside jokes, and allusions to either other Star Wars films or Shakespeare’s plays.

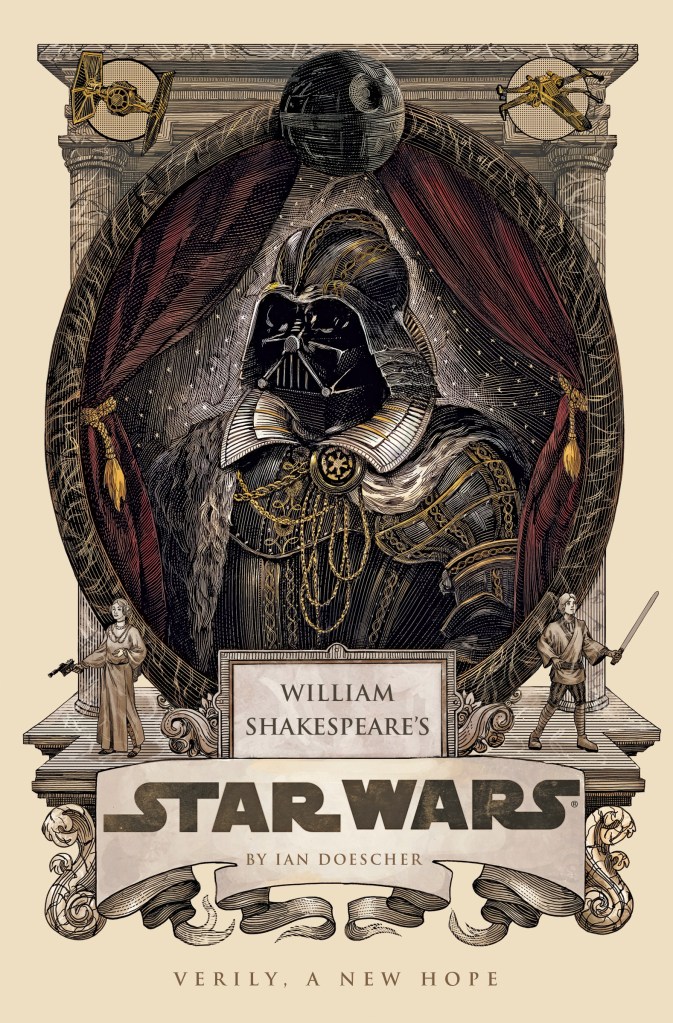

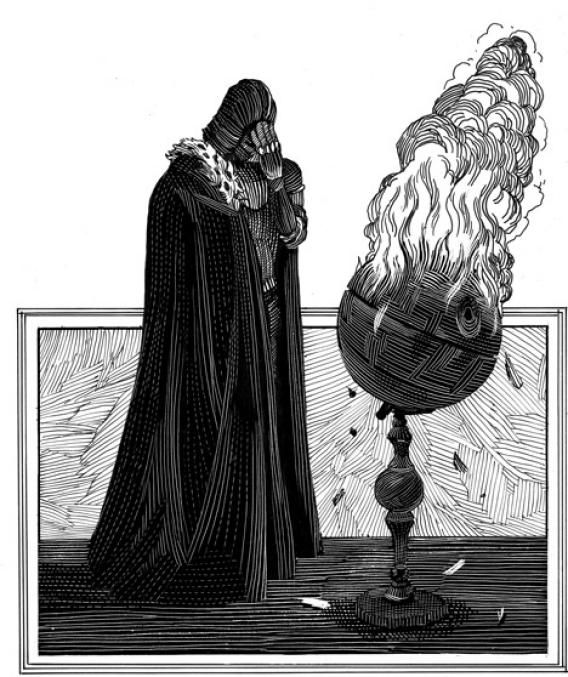

William Shakespeare’s Star Wars is illustrated by Nicolas Delort; his depiction of the iconic Star Wars characters as he imagines they would have looked if their costumes had been designed in Shakespeare’s time is spot-on. Darth Vader’s looks like a mix of his 1977-era design and Othello’s imposing battle uniform, complete with an ermine-lined cape and a modified version of his iconic breath mask and helmet.

Delort’s artistic sensibility matches the book’s tongue-in-cheek approach to the Shakespeare-Lucas mashup. Not only does he give John Mollo’s 1976 costume designs a suitable late 1500s look (Han Solo’s Corellian space pirate outfit, enhanced with Elizabethan era fashion details, is hilarious.), but he also shows readers how, with the use of wooden spaceship models suspended at the end of poles, Shakespeare’s stage production of Star Wars might have depicted the special effects sequences in George Lucas’s 20th Century movie.

The Book

The hardcover edition of William Shakespeare’s Star Wars is compact; it is only 176 pages long, including the Dramatis Personae page, the Afterword (where Doescher not only explains how Joseph Campbell’s study of Shakespeare’s works directly influenced Lucas during the making of Star Wars, but he also discusses how the book came about, explains some of the techniques used to mash up Star Wars with the Bard of Avon, and what iambic pentameter is), and the Acknowledgments page. It measures 5.5 x 0.7 x 8.3 inches, so it doesn’t take up a lot of shelf space.

The book is protected by a dust jacket, which features a nifty graphic featuring an Othello-like Darth Vader In the center, with smaller images of vehicles (a TIE fighter, the Death Star, and an X-wing fighter) shown above the Dark Lord, and, standing on opposite corners of a proscenium, Princess Leia and Luke Skywalker round out the images on the front cover.

Beneath the jacket, the slim volume looks like a weathered vintage edition of a Shakespeare play, like those found in a public library or a serious aficionado’s book collection. The cover looks “aged” and the typography on the front is designed to look like a book from the 1930s or ‘40s. Seriously, the attention to detail paid to William Shakespeare’s Star Wars by Quirk Books’ designer Doogie Horner is remarkable.

Illustration for William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope by Nicolas Delort. (C) 2013 Quirk Books and Lucasfilm Ltd. (LFL)

My Take

Obi-Wan: True it is,

That these are not the droids for which thou search’st.

Trooper 3: Aye, these are not the droids for which we search. – Act III, Scene 1, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars

I bought William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope and its two sequels (The Empire Striketh Back: Star Wars, Part the Fifth and The Jedi Doth Return: Star Wars, Part the Sixth in Quirk Books’ William Shakespeare’s Star Wars Trilogy: The Royal Imperial Set in 2014. I don’t remember how I came across it on Amazon; at the time I was dealing with my mother’s final illness (she died in July 2015, a month before I received William Shakespeare’s Tragedy of the Sith’s Revenge: Star Wars, Part the Third) and running a household under the worst of circumstances. I might have stumbled upon it while looking for something new to read as a freelance book reviewer for the now closed Examiner website.

I’m not, by temperament or inclination, a devotee of William Shakespeare’s works. Like many high school students in the English-speaking world, I had to read (and study) two of the Bard’s plays (Macbeth and The Taming of the Shrew) for my senior year regular English class. I can’t say I disliked those works; on the contrary, Ms. DeWitt, our instructor, was a cool lady and knew how to present the material well, so I enjoyed the time we spent in class learning about those two plays.

On the other hand, the only time I’ve bought a direct adaptation of a real Shakespeare play (West Side Story, which is based on Romeo and Juliet, doesn’t quite count.) was when I purchased Kenneth Branagh’s Henry V (1989) on Blu-ray a few years ago. Aside from that, I have a few Star Trek episodes that feature references to or even scenes from Shakespeare’s plays, as well as the Blu-ray of John Madden’s 1998 Shakespeare in Love.

Still, the notion of Star Wars reimagined as a 16th Century stage play intrigued me, and I definitely needed something to lighten my mood (the books are catalogued in the Humor genre, after all), so I bought the box set. I had a feeling that I would enjoy Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope, so I might as well get the entire trilogy while I was at it.

I don’t remember reading William Shakespeare’s Star Wars from cover to cover when I first got it. I do recall showing the box set to my mom – who was by then in the grip of memory-robbing, emotionally-debilitating dementia – at a time when she seemed to semi-understand the concept of a William Shakespeare pastiche based on Star Wars. I can still see, in my mind’s eye, a hint in my mother’s eyes that she liked the cover art by Nicolas Delort, and that It had something to do with a franchise that we both enjoyed. I’m not sure, though, that she grasped the Shakespeare angle of Ian Doescher’s books, and by the time I started receiving the Prequel era pastiches in early 2015, she was no longer able to glance at me with that appreciative look that said, Oh, look! A Star Wars book!

Suffice it to say that it wasn’t until 2017 that I finally read William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope cover to cover. Back in 2015, when Examiner granted me the Miami Books Examiner gig, I read just enough of Doescher’s book to review it with some authority. Many of the observations I made then – the book’s design, my thoughts on how well the author had executed the Star Wars/Shakespeare mashup, and my overall impression of the work – were honest (and positive), but they did not reflect a “deep read,” which was difficult, if not impossible, for me to do in late 2014 and early 2015.

As I mentioned before, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars is a book that booksellers, including Amazon, consign to the humor section. It’s considered as a satire, although in this case it’s not a “let’s make fun of Star Wars, like Mad or Crack’d magazines” style of humor.

Instead, Doescher goes for laughs in a subtle but still wink-and-a-nod style by using puns, clever wordplay, and references to other works in both the Star Wars canon and Shakespeare’s plays and sonnets.

For instance, the author knows – as he acknowledges in his afterword – that only the newest and youngest of fans are not aware of the father-son relationship between Luke Skywalker and Darth Vader. Thus, he plays on the fact that most of his readers, including older fans like me, know something about the story’s main characters that Luke, Leia, and Vader (at this point in the narrative) clearly do not.

This is how Doescher deals with the whole “A young Jedi named Darth Vader: he was a pupil of mine until he turned to evil. Helped hunt down and destroy the Jedi Knights. Now the Jedi are all but extinct. He betrayed and murdered your father,” narrative that Obi-Wan tells Luke early on in Star Wars:

Luke: How hath my father died?

Obi-Wan: [aside] – O question apt!

The story whole I’ll not reveal to him,

Yet may he one day understand my drift:

That from a certain point of view it may

Be said my answer is the honest truth.

[To Luke} A Jedi nam’d Darth Vader – aye, a lad

Whom I had taught till he evil turn’d –

Did help the Empire hunt and then destroy

The Jedi. [Aside] Now, the hardest words of all

I’ll utter here unto this innocent,

With hope that one day he shall comprehend.

[To Luke] He hath thy Father murder’d and betray’d,

And now are Jedi nearly all extinct.

Young Vader was seduc’d and taken by

The dark side of the Force.

As you can see, Doescher writes this speech for Obi-Wan in a seemingly straightforward way, but it’s slyly funny because he not only knows that most of his audience already know Vader’s backstory, but he also gives the old Knight part of a line that is from the scene in Return of the Jedi when Luke brings this conversation up with Kenobi’s Force ghost on Dagobah after a dying Yoda finally confirms the truth about Anakin Skywalker .

As Timothy Zahn, a Hugo Award-winning novelist who is best known as the creator of Grand Admiral Thrawn in both the Star Wars canon and Legends (the old Expanded Universe), wrote at the time:

“The Bard at his finest, with all the depth of character, insightful soliloquies, and clever wordplay that we’ve come to expect from the master.” – Back cover blurb, William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope.

Of course, Doescher doesn’t just reference the Star Wars saga and puts a Shakespearean spin to it. There are scenes in this play that are linked to Shakespeare’s plays, as well. One of the most famous speeches written by the Bard, the St. Crispin’s Day oratory from Henry V, is referenced during the Battle of Yavin sequence:

Luke: Once more unto the trench, dear friends, once more!

The death of our dear friends we see today,

And by my troth their souls shall be aveng’d!

….So Biggs, stand with me now, and be my aide,

And Wedge, fly at my side to lead the charge –

We three, we happy three, we band of brothers,

Shall fly unto the trench with throttles full!

This is a book that, by its very nature, begs to be read aloud or even performed on stage by theater students or an amateur Shakespearean company. It helps, of course, to watch both a screening of Star Wars and a Shakespeare play in order to recite the iambic pentameter without sounding stilted or reading from a religious book.

Of course, this might not be possible, but Random House Audio did record a professionally performed audiobook in a 15-CD box set with all three Episodes of the Star Wars Trilogy. I listened to the audio version of Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope while reading the book; and boy, if that is not a mind-blowing experience, I don’t know what is.

Comments

One response to “Book Review: ‘William Shakespeare’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope’”

[…] of Doescher’s Star Wars: Verily, A New Hope, The Empire Striketh Back: Star Wars Part the Fifth, and The Jedi Doth Return: Star Wars Part the […]

LikeLike