I was 24 in the spring of ’87—still holding onto the hope that someday, somehow, math would make sense to me. Spoiler: it didn’t. Not then, not now. Even the so-called “remedial” kind felt like trying to read sheet music in the dark.

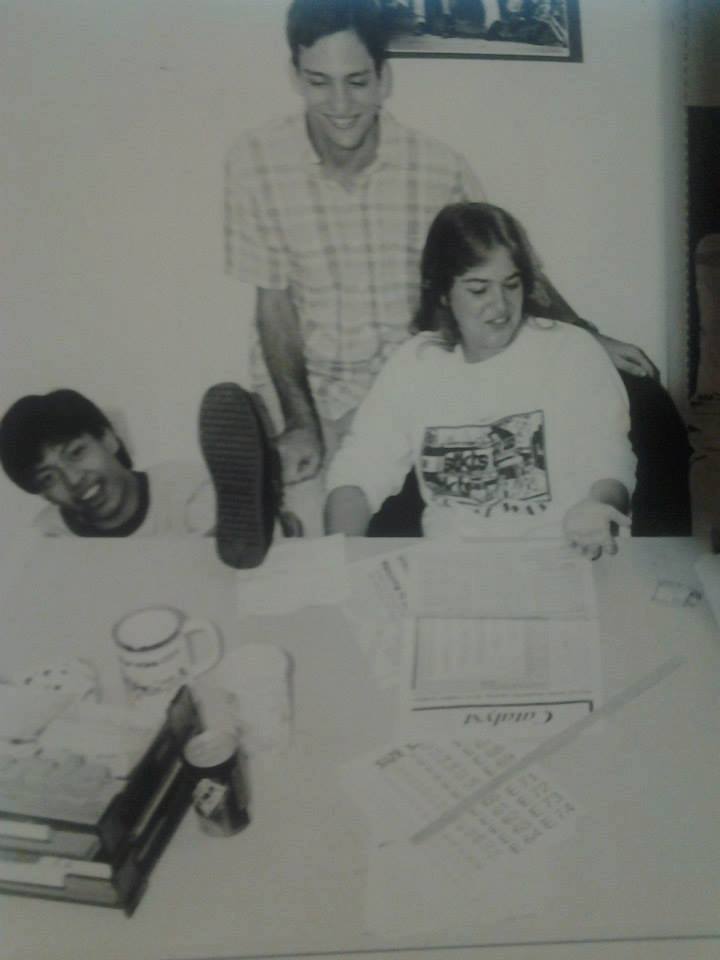

But while numbers left me bewildered, words felt like home. I was the copy editor for Catalyst, the student newspaper at Miami-Dade Community College’s South Campus, and that newsroom became my haven. Between articles and deadlines, I dove into courses that cracked open the world: Russian history, Human Sexuality, International Relations, and Mass Communications. Each class was a new passport stamp in a mind eager to travel.

It wasn’t perfect—nothing ever really is at 24. But it was the beginning of something. Of finding my voice. Of chasing the spark that writing always gave me. And that spring? That spring still feels like the moment I realized I had something to say.

That same semester, Professor Peter Townsend—our fearless journalism instructor and Director of Student Publications—had an idea. He called it About Time. It wasn’t news. It wasn’t opinion. It was memory—raw, unfiltered, and ours.

The section didn’t come with deadlines or directives. No one told us to chase down quotes or call the Public Relations office to quiz Johnny “Mac” Allen about the campus cable deal. About Time was something different. Voluntary. Vulnerable. And, maybe for the first time, truly ours.

Each piece offered a glimpse into someone’s private world: sun-drenched days at Disney World, sleepless nights shadowed by family strife, soft-spoken confessions about love, loss, and everything in between. It was a mosaic of college hearts laid bare on newsprint.

Looking back, it wasn’t just a new section in the paper. It was a quiet revolution. And in a campus newsroom buzzing with headlines and ambition, About Time reminded us that some of the most important stories are the ones we’ve been carrying all along.

I contributed two About Time pieces that semester. One was a first-anniversary retrospective on the Challenger disaster. It caught the eye of judges in several journalism competitions Catalyst entered—partly because I adapted an illustration by former graphics editor Alex Severe, placing the doomed mission’s crew patch on his 1986 cartoon. But it was also, I’ll admit, a strong column.

Still, that was my second submission. My first, He once met a girl named Maria, holds a special place in my memory—and in my biased eyes, it was my best. It told the story of a girl I met during my second semester at Dade, two terms before I joined the Catalyst staff. I wrote about my youthful, naive hope that love might bloom between us. It didn’t go as planned, which is why Professor T gave the column the slug line Heartbreak Time.

He once met a girl named Maria

(Catalyst, About Time section, circa 1987)

Alex Diaz-Granados

Copy Editor

Heartbreak Time

It was love at first sight. I first saw her as she was walking into class one spring day. The classroom was nearly empty – most of our fellow PSY 1000 students hadn’t arrived, so I couldn’t help but notice her.

She was exquisitely beautiful – dark curly hair, fawn-like brown eyes and a smile that caught my attention at first glance. I got goose pimples of excitement at second glance and sent my heart to the moon at third.

“Hi,” she said in a soft friendly voice.

“Uh, hi,” I replied, feeling about as articulate as a mango. “Hi.”

She smiled, waved at me (sort of) and sat down at her desk. I stole a furtive glance at her, hoping she wouldn’t catch me.

Suddenly, her eyes met mine.

I froze, thinking that soon I would be flying across the room.

I closed my eyes, expecting the very worst.

Nothing happened.

I opened my eyes.

There was a 10 second pause – the whole world seemed to have come to a screeching halt. We exchanged glances, then, coming to my senses (or what remained of them, anyway), I turned around.

Time passed.

A few weeks later, my notetaker couldn’t make it to class, so I had to cope by memorizing lectures.

After a few days of this, my nameless dream girl, sensing that I was in trouble, walked up to me after class and asked, “Would you like me to take notes for you?”

“S-s-sure,” I stammered, wishing that I’d said that with calm and confidence. “I’d like that very much. Thanks.”

She smiled and turned to leave. “Wait!” I said before she reached the door.

She turned to face me and smiled at me. “Yes?”

“What’s your name?” I asked in a more subdued tone of voice.

“Maria,” she said. And with that, she left the classroom.

From then on Maria and I established a routine. On those days when I arrived on campus early, she and I would meet by the benches between Buildings Nine and Two and talk about who we were, where we were from and where we were going.

Maria, I soon discovered, was from Managua, and had come to the United States not long after the Sandinistas took over Nicaragua in 1979. She told me about the horrors of war and how glad she was to be in America.

In turn I told her how much I loved to write and how I planned to have a career as a journalist. I also told her about the little things that interest me – books, movies and music.

There would be moments when we’d sit on a bench and just watch other students walk by or the occasional squirrel scampering along the sidewalk. We would say nothing at all – we’d just share a smile.

In class, I would find myself turning around to steal a glance at her. Sometimes she wouldn’t notice, but most of the time she would look up from her notes and smile.

But spring semesters are short, so when finals drew near, I asked her to have lunch with me before school ended.

“Yes,” Maria said. “I’ll meet you here after class tomorrow.”

I felt lightheaded. It could have been something in the spring morning air, but somehow I doubt it. “Great,” I said happily. I went home that day humming “Maria” from West Side Story.

The next day, showing up early as usual, I looked for Maria at our usual “rendezvous,” but without much success. Instead, I ran into my friend Richard, who was looking all over for me.

“Where’s Maria?” I asked.

“In class,” said Richard. “She told me to tell you that she can’t meet you for lunch after all.”

I was stunned. It couldn’t be true. If it was true, then we’d only have a few minutes to exchange addresses and photographs – and then no more surreptitious glances in class, no more squirrel watching.

Worst of all, I would be here in Miami, and Maria would be in California.

After class (during which I had hastily scribbled a short note in which I gave her my address), Maria walked up to me.

“I’m sorry I can’t have lunch with you. I really want to, but my best friend is flying in from L.A. this afternoon, so I’ve got to go to the airport and pick her up.”

“It’s okay,” I lied. “Look, you have my address – and my photograph – in here,” I added, handing her the note I’d written.

“I’ll write you first chance I get,” she said. She then reached into her purse and handed me a photograph. On the back she’d written, “With all my love, your friend, Maria.”

I looked into her eyes one last time, then walked away, softly humming “Maria” to myself.

I waited all summer for her letter.

I’m still waiting.

Postscript, 2025

No, I never got that letter. And by 1988, just before I crossed the Atlantic for a Semester in Spain, I stopped waiting for it. Maria’s photo—signed in looping script, “With all my love, your friend, Maria”—still sits wrapped in an old moving box somewhere, the frame slightly worn, the memory intact. I doubt she even remembers me.

But I remember her.

And maybe that’s the point.

I wrote this column around the same time I wrote my first Jim Garraty piece for a creative writing class. Marty wouldn’t appear on the page until more than a decade later, in Reunion: A Story, but in hindsight, it’s not hard to trace the emotional lineage. That quiet ache of youthful longing, the intimacy of shared silences, the way hope can flicker and fade and still leave a light behind—it’s all there. Maria may not exist in the Garratyverse, not by name, but the emotional weather she stirred still lingers in its atmosphere.

Stories begin with what moves us. And sometimes, the ones we never finished are the ones that shape us most.

You must be logged in to post a comment.