Unexpected Lessons in Writing

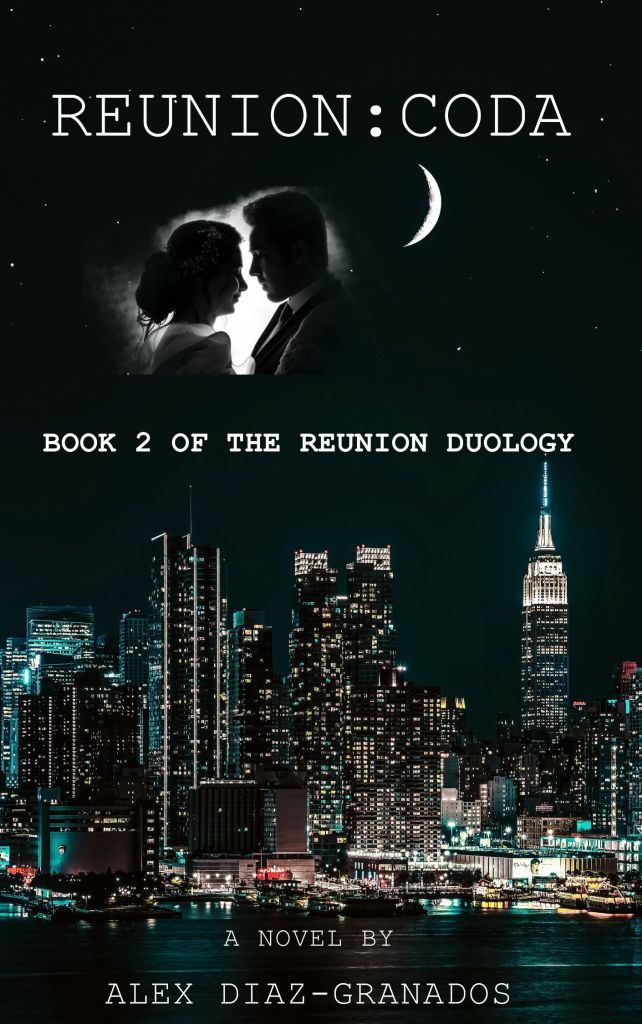

On April 4, nearly four months ago, I published Reunion: Coda, the second book in my Reunion Duology and my first novel. The first book, Reunion: A Story, is a novella. I spent a little over two years writing this novel. I began in March 2022 while living in Tampa, wrote about a third of it in Madison, NH, between December 2022 and October 2023, and finally completed it here in Miami on April 2.

As I’ve said in previous posts about the creative process behind Reunion: Coda, this wasn’t my first attempt at novel writing. It was my fourth attempt since I graduated from high school in 1983 and my third attempt since my mother died in 2015. It was, however, my first successful try, even though it took me far longer than I expected, thanks to some unexpected unraveling in my non-writing life.

I’ve already written a “Lessons Learned While Writing Reunion: Coda” post, but this morning I realized that the experiences I had between March 2023 and April 2025 imparted a few more nuggets of wisdom.

Characters Rule…Plot? Not So Much

When I began writing Reunion: Coda, I believed that good stories strike a fine balance between plot and character development. After all, you can’t have a story without at least a basic plot, right? The way my late ninth-grade English teacher, Esther Allen, told us back in the spring of 1980, writers must have structure, conflict, protagonists, antagonists, and at least a semblance of a theme, regardless of which genre they write in.

Of course, this was before I bought and read Stephen King’s seminal On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft back in 2021. In that book, King teaches aspiring writers that the best stories are character-driven and that plot should be the least of their worries.

King advocates character-driven stories, prioritizing character and situation over plot. He believes that strong characters and compelling situations naturally lead to a story, and that plot-driven narratives can feel artificial. King emphasizes that writers should follow their characters and the story’s unfolding rather than forcing events to fit a predetermined plot.

Here’s a quote from On Writing: A Memoir of the Craft:

“I think the best stories always end up being about the people rather than the event, which is to say character-driven.”

And here’s another:

“Stories are found things, like fossils in the ground… Stories are relics, part of an undiscovered, pre-existing world.”

King goes on to describe the writer’s job as that of an archaeologist, carefully excavating the story rather than constructing it. He warns against forcing plot onto a story like scaffolding—it risks breaking the fossil. Instead, he encourages writers to uncover the truth of the story piece by piece, letting character and situation guide the process.

In my three stories featuring Jim Garraty, I allow the characters to shape the narrative through their actions and reactions to specific situations instead of being a control freak and herding them to a predetermined conclusion. This might sound strange to you, especially if you’re an aspiring author or a Constant Reader who believes plot and structure should be a storyteller’s main tools. Well, they are tools, useful tools at that. But they’re not as important as we’re led to believe by junior and senior high school English teachers.

Wandering Off the Map

There’s a moment—often quiet, sometimes jarring—when a story pulls away from where you thought it was headed. Maybe the protagonist surprises you with a decision you didn’t script, or maybe a minor character starts murmuring their way into a larger role. When you write without a rigid outline, these turns can feel like betrayals of your original vision. But what if they’re not detours, just discoveries?

I used to see these surprises as mistakes. Now I welcome them like guests who brought dessert. In writing Reunion: Coda, I learned that the real magic happens in the moments I didn’t plan—the scenes that whispered instead of shouted, the arcs that meandered and bent like memory itself. These aren’t signs the story has lost its way. They’re proof it’s alive.

Fear and despair—that sinking feeling of “I don’t know where this is going”—are perfectly human reactions. But in storytelling, they’re often precursors to transformation. To trust a story is to allow it to roam. It’s like raising a child who starts asking questions you never considered. You can guide them, sure. But you can’t hold their hand forever.

So if your characters lead you into fog, follow them. If the ending changes course, adjust your compass. The story knows more than you think. Let it teach you something you didn’t expect to learn.

So here’s the punchline: If you ever find yourself fretting because your plot has wandered off like a distracted dog in a park, congratulations—you’re doing something right. The best tales, like the best dinner parties, are remembered not for the seating chart but for the unexpected guests and the stories they tell after dessert. So stop wrestling your story into a straitjacket. Let it trip over its own shoelaces, let it sneak out the back door, let it borrow your car keys and promise to be home by midnight. Trust your characters to lead, and don’t be afraid if you catch yourself lost. You’re not lost; you’re exploring.

After all, the map is not the territory—and sometimes the best stories are the ones that didn’t follow directions.

The truth is, stories rarely unfold the way we first imagine them—and thank goodness. Because the ones that breathe, stumble, and surprise us often feel the most alive. If Reunion: Coda taught me anything, it’s that trusting the process—and the people in it—might just be the most important tool we have.

You must be logged in to post a comment.