“If writing were easy, everyone would do it.” – as a wise soul (or three) allegedly said

At my core, I am a storyteller—a weaver of tales, a conjurer of characters, a writer with ink in my veins and metaphors rattling around in my head.

The precise age when I let go of my other, admittedly less practical (especially for a kid with my physical quirks) dreams—soaring as a pilot, joining NASA and traipsing across the Moon, or marching off to the armed forces—escapes me now. I suspect it was when I was about 10 or 11. At the time, I was wrestling with English as a second language at Tropical Elementary in South Florida. But I do remember this: by seventh grade, as a freshly minted Riviera Junior High student (Tropical’s next-door neighbor and my new stomping grounds for the 1977-78 school year), the creative fire was blazing in my imagination. Around then, I discovered Star Wars and the gripping tales of Stephen King—both serving as the perfect antidotes to a string of emotional paper cuts: the loss of my beloved grandfather, the bittersweet sale of our Westchester home that summer, and, worst of all, my inaugural teenage heartbreak. Middle school is dramatic enough without vampires and galactic battles, but those stories gave me a place to land when real life felt like too much.

One thing I can say with almost scientific certainty: I was a 15-year-old, still untangling the emotional knots from my personal annus horribilis of 1977, when—almost on a whim—I decided I wanted to be a novelist. If there was a lightning bolt of destiny, it probably struck while I was daydreaming in homeroom.

Not, as is the case for many aspiring writers (Stephen King included), out of a fit of literary indignation after slogging through a dreadful novel and thinking, Hey, I could do better than this guy. Just hand me a typewriter, a mountain of paper, and a quiet room, and I’ll write something worth reading!

My own “Eureka!” was sparked by Stephen King’s Salem’s Lot—his 1975 riff on Bram Stoker’s Dracula, which unleashed a swarm of vampires upon the unsuspecting residents of Jerusalem’s Lot, Maine. King’s style was open-door inviting, and so emotionally direct that I found myself drawn to a genre I’d typically cross the street to avoid—horror. Since seventh grade, I’ve been hooked on his stories and the way he tells them, even if I haven’t checked every book off his massive bibliography.

It wasn’t the monsters or the mayhem that opened the creative floodgates in my mind—it was King’s writing itself. His knack for storytelling made me think, Now here’s a guy who knows how to spin a yarn. No pretentious prose or dialogue so squeaky-clean it could double as a TV commercial. He makes you believe vampires could actually take over a small town in Maine because his characters talk, bicker, eat Dinty Moore beef stew, puff Marlboros, and shop at real places like Jordan Marsh in Bangor. They live and breathe (and sometimes bite), and you’re right there with them.

And with that realization came another, trailing close behind: Maybe, just maybe, if I put in the work and discover which stories are burning to be told, I could write a novel, too!

At 15, I dove headfirst into this journey without grasping just how tough and winding it would be. I brimmed with youthful confidence and a touch of naïveté, convinced I knew what it took to become a writer. Back then, I didn’t understand there’s a world of difference between wanting to write in America—a country that often overlooks the creative arts—and actually becoming a writer, especially in the late twentieth and early twenty-first centuries.

Tackling fiction, especially novels, tested me in ways I never expected. I discovered—sometimes painfully—that long-form storytelling demands much more than boundless energy and optimism. Writing for my high school and college newspapers in the 1980s felt easier; I covered entertainment, news, and op-eds, edited fellow students’ stories, and wrote headlines as a section editor. Occasionally, I found my own news leads. Through those years, I sharpened my interviewing skills (three sources per news piece was the golden rule), learned how to hit deadlines, and worked with a team. Yet, aside from a lone creative writing class in 1987, I barely touched worldbuilding, dialogue, story structure, or the raw honesty that fiction requires.

But here’s the part I didn’t understand back then—something no seventh‑grader, no matter how starry‑eyed, could grasp. Falling in love with storytelling is one thing; learning what it actually takes to become a writer is something else entirely. Inspiration may light the fuse, but the long haul? That’s where things get messy, complicated, and, at times, downright humbling.

And, to be painfully honest—with all the self-deprecating warmth I can muster—I spent far more years tangled up in my own creative tripwires than I care to confess. My brain was a factory of grand ideas for sprawling science fiction sagas. For instance, there was the time, fueled by equal parts caffeine and hubris, I mapped out a novel called The Andromeda Project while juggling deadlines at the college newspaper. In my mind, it was the sort of cosmic adventure Isaac Asimov or Arthur C. Clarke might dash off in a single afternoon, blindfolded—but for a rookie like me, it was a mountain too steep to climb.

Then there were wild schemes for historical epics à la David Westheimer’s Lighter Than a Feather or James Webb’s Fields of Fire. Ambition? Absolutely—I could have bottled and sold it. But time, patience, and (let’s be real here) the discipline to actually finish what I started? Not so much. Turns out, having big dreams is easy; matching them with hard work is a whole different ballgame.

Insecurity was my constant companion, lurking in the wings and whispering doubts in my ear. The business side of publishing felt like a labyrinth with no exit, and the specter of failure loomed so large, I could practically see its shadow on my bedroom wall. Even though some trusted souls—including Miami‑Dade professors who actually knew a thing or two about storytelling—told me I had talent, that I could be a good writer if I kept at it, I greeted their encouragement with the skepticism of a kid who’s just been told broccoli tastes like candy.

Sure, I appreciated the occasional kind word about my CRW‑2001 scribblings, but deep down, that cynical voice always piped up: Oh, you’re just being polite. Or, Maybe my stuff is okay for a college kid, but I’ll never be as good as King, Clancy, Gerrold, Coyle, Coonts, or Harris—let alone Hemingway. It was the classic case of comparing my rough drafts to someone else’s polished novels—a self‑defeating hobby if ever there was one.

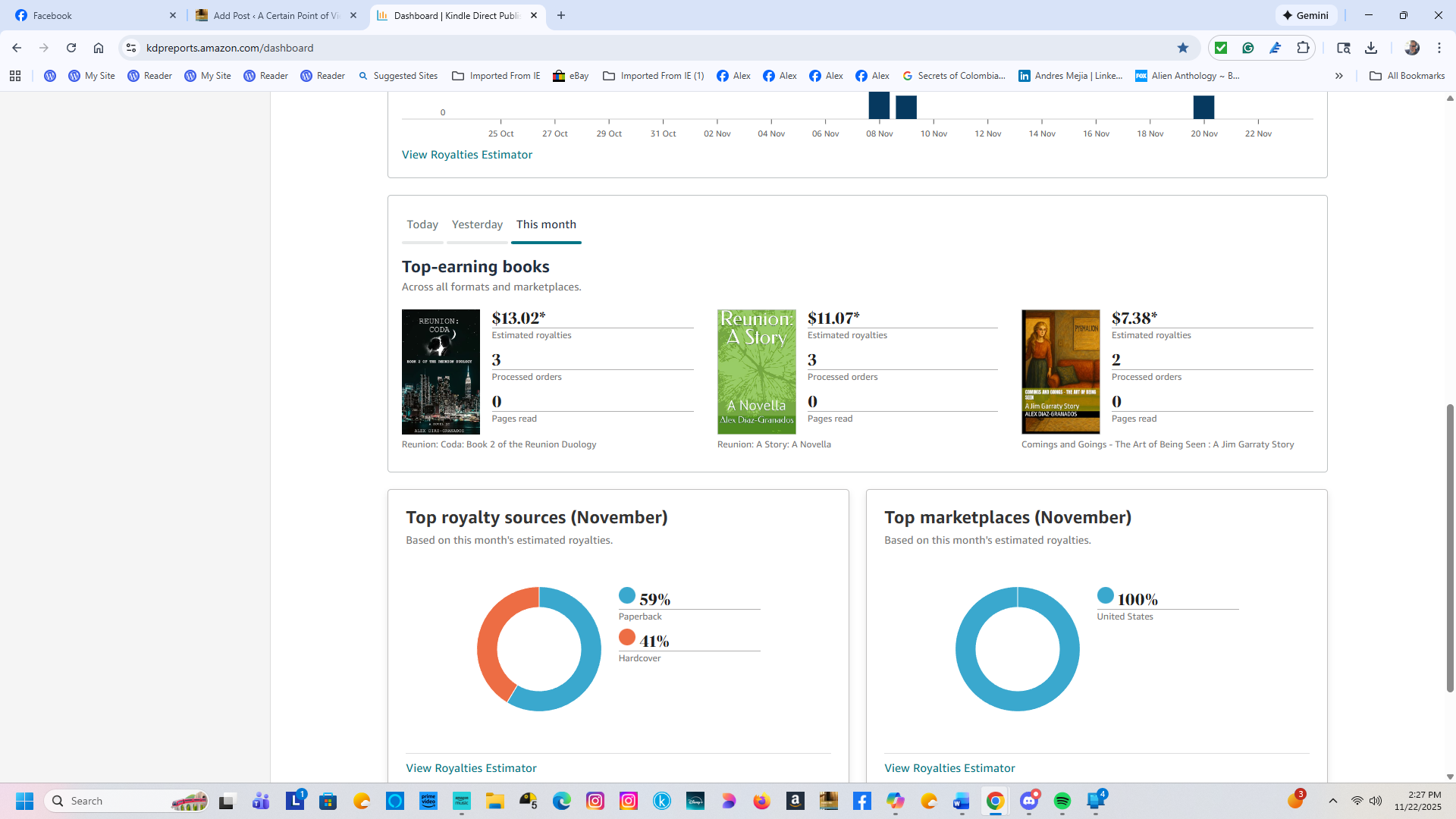

Toss in a laundry list of self‑made roadblocks—impatience, sky‑high expectations, a knack for tearing myself down, and more than a dash of not taking it seriously—and you’ll see why it took me eleven years to move from finishing that college creative writing class to finally cobbling together the first raw, unrefined draft of what would become Reunion: A Story.

And then, as if to make up for lost time, I let another twenty‑five years roll by before I marched back into the writing room, this time with something resembling purpose. The spark? A nudge from a mentor who, after reading the rough‑and‑ready first edition of Reunion (courtesy of CreateSpace), not only liked it but took the time to suggest edits, revisions, and—best of all—cheered me on to keep writing truer, better stories. So, if you’re keeping score at home, that’s decades of stubbornness, self‑doubt, and delay punctuated by a much‑needed shot of encouragement—and, finally, the resolve to give my stories the fighting chance they deserved.

(Also, I didn’t meet that publication deadline!)

Looking back, it’s almost funny how certain I was that inspiration alone would be enough to see me through. But the truth is, writing became a mirror reflecting not just my ambitions, but my insecurities and my growth. Each attempt—successful or not—taught me something new about discipline, resilience, and the willingness to revise, rethink, and keep moving forward even when the path was anything but straight. Those years shaped me, not only as a writer but as a person willing to chase after a dream, one page at a time.

And here’s something aspiring writers need to know, in plain, conversational English: it’s perfectly fine to want to write a novel. If that’s your dream, go for it with your whole heart. But it’s also okay to recognize when the reality of your life doesn’t match the demands of long‑form writing. If your health makes it hard to sit and focus for long stretches, or if your responsibilities and passions tug you in a dozen directions, or if you simply can’t carve out hours each day to put words on the page, then novel‑writing might not be the right fit—and that’s not a moral failing. That’s just life being honest with you. There are countless ways to tell stories, to create, to express yourself. A novel is only one path, not the only one.

In the end, the journey wasn’t about proving myself to anyone else, but about learning to trust my voice and honoring the stories that refused to let go. If there’s one certainty I carry forward, it’s that the act of writing—like life itself—isn’t a test of perfection but of perseverance and honesty. And with each new page, there’s always the promise of discovery.

You must be logged in to post a comment.